A little-known Thai woman is the real author of an important Buddhist treatise - not the high-profile monk previously credited, according to new findings.

Thammanuthamma-patipatti [Practice in perfect conformity with the Dhamma] contains a series of dialogues that supposedly took place between two of the most prominent monks in 20th century Thailand, and is widely considered a valuable and profound Buddhist text.Until now the book has been attributed to one of these two monks – Venerable Luang Pu Mun Bhuridatta, a national saint of Thailand who led the Forest Tradition revival movement in the first half of the 20th century. The movement has monasteries worldwide including five in the UK.

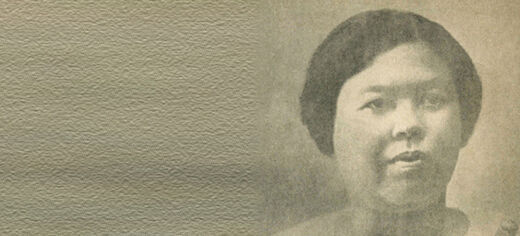

But a researcher at the University of Leeds has traced the authorship to Khunying Yai Damrongthammasan, a wealthy and extremely devout woman who developed an impressive knowledge of Buddhist scriptures during her lifetime.

Dr Martin Seeger from the University of Leeds’ School of Languages, Cultures and Societies said: “There is compelling evidence that Khunying Yai wrote this book. I believe this makes her the first woman in Thailand, or one of the first two, to write an important Buddhist treatise.

"The deplorable lack of sources on her life has made this search rather difficult. For nearly 60 years she has been virtually unknown although she produced one of the most profound Buddhist texts.

“Despite her extraordinarily interesting biography, her brilliant contributions to Thai Buddhist literature, her donation of historically significant Buddhist edifices and the fact that she was rather close to a number of the most well-known and influential Buddhist monks of her time, there is hardly any surviving historical evidence on Khunying Yai’s biography.”

The literary investigation started when a Thai acquaintance of Dr Seeger’s, Mr Naris Charaschanyawong, raised doubts about the authorship.

Dr Seeger said: “We spent three months interviewing people in Thailand who had met Khunying Yai or knew people close to her. Over the course of those interviews and the study of a number of biographical texts of highly respected monks it became increasingly clear that she must have been the real author.

“A number of factors taken together convinced us of this outcome. Some of the comments are unlikely to have come from monks; there are inconsistencies, for example at least one edition says that parts of the book were written by a disciple; other monks referred to Khunying Yai having written a book; there was no mention of the treatise in Luang Pu Mun Bhuridatta’s funeral book; and in 1984 Khunying Yai’s adoptive son called for her to be named as author in the foreword to his own book, but as this book was hard to find his plea went unrecognised and future editions carried Luang Pu Mun Bhuridatta’s name.

“At the moment, it is not clear how authorship was ascribed to Luang Pu Mun Bhuridatta. According to the most authoritative biographies of him, he never claimed that he wrote the book.”

The text was first printed in five parts between 1932 and 1934 without a named author. But later editions used photos of the two monks featured on the book’s cover, and some of these editions credited authorship to the more prominent monk, Luang Pu Mun Bhuridatta.

Dr Seeger said: “The real reason that Khunying Yai decided to omit her name from the first edition might never be known, but there are several possibilities. At the time people may have considered it inappropriate for a woman to discuss Buddhist doctrine on such a profound level.

"Or she might have thought that Buddhist doctrine should be independent of an individual. Another possibility is that the conversations described actually took place in the group of women who met regularly in the temple of Wat Sattanatpariwat to discuss Buddhism, and she wanted to remain anonymous out of respect for them.”

Unlike most women in Thailand in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Khunying Yai was taught to read and write. She was born in 1886 into nobility and grew up in Bangkok.

From a young age she was taught by monks and reportedly developed a detailed understanding of Buddhist doctrine and an unusual capacity for remembering texts.

She married a famous judge, also a nobleman. When he died she gave away her belongings and moved into a Buddhist monastery in Thailand’s southern province of Prajuabkhirikhan where she studied scriptures and practised meditation until her death in 1944.

Dr Seeger received a British Academy grant to conduct his research.

For more information:

Dr Seeger is available for interview, please contact the University of Leeds press office on +44 113 343 4031 or email pressoffice@leeds.ac.uk